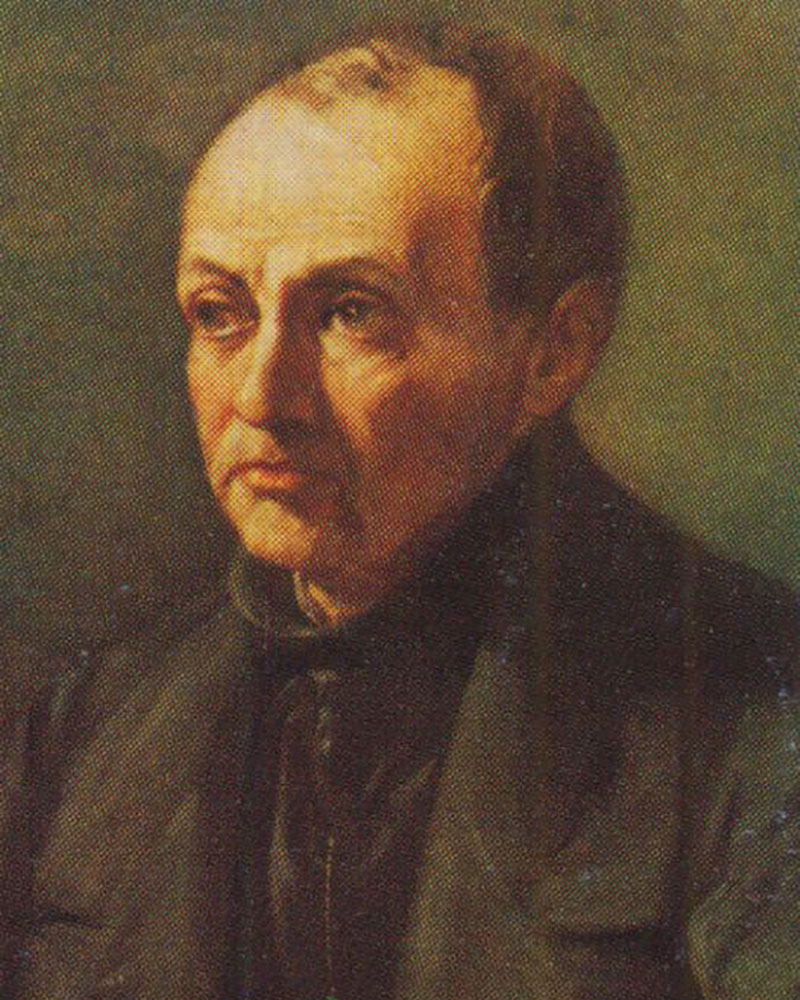

Though we tend to think of atheists as not only unbelieving but also hostile to religion, we should remember a tradition of atheistic thinkers who've tried to reconcile a suspicion of the supernatural side of religion with a deep sympathy for and interest in it's ritualistic aspects. The most important and inspirational of these was the visionary, eccentric, and only intermittently sane French 19th century sociologist, August Comte.

Comte was born into a strict Catholic family in Montpelier in Southern France in 1798. As a young man, he received a highly progressive education and became obsessed with the idea of building a new kind of France based around science and republicanism. His family violently disagreed and broke off relations with him so he went to live in Paris, where he became a student of, and later, secretary to the Utopian thinker, Henri de Saint-Simon. But Comte had a quarrelsome nature and fell out with Saint Simon, failed to get a university post, and for the rest of his life, maintained a precarious existence writing dense, often unreadable, works about the reform of humanity. He was not entirely sane and spent long periods in asylums, and in 1827, attempted suicide by jumping off the Pont des Arts in Paris.

In 1844, he fell deeply in love with a married woman called Clotilde de Vaux but the relationship was never consummated. After her premature death, Comte made his love for Clotilde into one of his center pieces of his thinking on religion.

Though a deeply eccentric man, Comte did manage to gain the trust and interest of the important British philosopher, John Stuart Mill, who admired his efforts around religion, and helped Comte to be better known in Britain.

Comte's thinking on religion had as it's starting point, a characteristically blunt observation that in the modern world, thanks to the discoveries of science, it would no longer be possible for anyone intelligent to believe in God. Faith would henceforth be limited to the uneducated, the fanatical, women, children, and those in the final months of incurable diseases. At the same time, Comte recognized, as many of his more rational contemporaries did not, that a secular society devoted just to financial accumulation and romantic love and devoid of any sources of consolation transcendent awe of solidarity, would be prey to some untenable social and emotional illness.

Comte's solution was neither to cling blindly to sacred traditions, nor to cast them collectively and belligerently aside, but rather to pick out the more relevant and secular aspects and fuse them together with certain insights drawn from philosophy, art, and science.

The outcome of decades of thought and the summit of Comte's intellectual achievement was a new religion: a religion for atheists, or as Comte termed it, "A Religion of Humanity": an original creed expressly tailored to the emotional and intellectual demands of modern men and women, rather than the inhabitants of Judea or northern India in 400 B.C.

Comte presented his new religion in two volumes: the "Summary Exposition of the Universal Religion" and the "Theory of the Future of Man." He observed the traditional faiths tended to cement their authority by providing people with daily, and even hourly, schedules of who or what to think about. Rotors typically pegged to the commemoration of a holy individual or supernatural incident. So Comte announced a calendar of his own, animated by a pantheon of secular heroes and ideas.

In the Religion of Humanity, every month was to be devoted to the honoring of an important field of endeavor; for example: marriage, parenthood, art, science, agriculture and every day to an individual who had made a valuable contribution within these categories.

Comte was impressed by the way the traditional religions had disseminated moral guidance, for example: dictating principles on how to conduct oneself in a marriage, or fulfill one's duties to the community. And he lamented the modern, liberal governments, in their desire to prove inoffensive to all constituencies, had settled on merely offering factual instruction before letting people out into the world to destroy themselves and others through their egoism and self ignorance. Therefore, in Comte's Religion of Humanity, there would be classes and sermons to help inspire one to be kind spouses, patient with one's colleagues, and compassionate towards the unfortunate.

Comte also recognized how badly we all need consolation and proposed that his girlfriend, Clotilde, take the function previously accorded within Catholism to the Virgin Mary. Portraits of Clotilde were to be placed everywhere in the new religion, and when one was down, one was invited to share one's sorrows and weep in front of his vision of kindness and sympathy. Because Comte appreciated the role that architecture had once played in bolstering the claims of traditional religion, he proposed the construction of a network of secular churches, or as he called them, "Temples for Humanity."

He suggested that each one be paid for by a banker, whose bust would appear above the door in recognition of his generosity. Rather than resenting bankers, Comte thought it was wiser to coax them into supporting good causes. Inside the temples of humanity, there would be lectures, singing, celebrations, and public discussions. While around the walls, sumptuous works of art would commemorate the greatest moments and finest men and women of history.

Finally, above the west-facing stage, there would be a large aphorism written in golden letters, invoking the congregation to adopt the essence of Comte's philosophical religious world view: the statement, "Connais Toi Pour T'ameliorer" (Know yourself to improve yourself.)

Regrettably, Comte's complex, thought provoking, and often deranged project was felled by a host of practical obstacles. Ridiculed by both atheists and believers, ignored by public opinion, devoid of funds, Comte fell into despair and self-pity. He took to writing long and frightening letters in defense of his scheme to monarchs and industrialists across Europe, including Louis Napoleon, Queen Victoria, the Crown Prince of Denmark, three hundred bankers, and the head of the parish sewage system. But few offered money, let alone replies.

Without seeing any of his proposals take hold, Comte died at the age of 59, in 1857. But Comte was well served by his followers, and in the decades after his death, his religion made some notable advances. The Chapelle de L'humanite was opened at 5 Rue Payenne in Paris, where it still stands to this day, and became a well known venue for secular baptisms, funeral services, weddings and sermons. Comte's religion crossed the channel, where it acquired 5,000 adherents, led with rare energy by a former Oxford Don. In 1878, with the help of a legacy from an aunt, the Don opened the Church of Humanity in Lamb Conduit Street in London, where secular services were held every morning.

Comte's religion had even greater success in Brazil, where it was put into practice by some students that Comte had taught in Paris in the 1840s. El Templo de la Humanidad opened in Rio in 1890, and others followed in São Paulo and Curitiba.

Unfortunately, infighting among the leadership connected to doctrinal squabbles about the place of Western authors and their liturgy, meant that the movement failed to grow into a truly popular religion. And yet it acquired a small and permanent place in Brazil's spiritual life. To this day, every Sunday morning in Rio de Janeiro, at 74 Rua Benjamin Constant audiences, who make up in intensity of what they lack for in numbers, arrive at the Templo de Humanidad to draw sustenance from the teachings of a Parisian sociologist's unusual secular religion.

Whatever its shortcomings, Comte's religion is hard to dismiss entirely, for it identified a psychic space in atheistic society, which continues to lie fallow and to invite resolution. Comte's work was an attempt to rescue some of what is beautiful, touching, reasonable, and wise from what no longer seems true. For these reasons and more it remains extremely timely.